The brain as argument? Seems like an unlikely analogy, yet that is precisely what Lehrer compares it to in How We Decide. The interesting aspect of this that to the extent that a person supresses this argument - this diverse sounding out of all sides - to that extent the person runs the risk of coming to a wrong decision. Unfortunately certainty is no guide when it comes to making a good decision. In fact, in studies of TV pundits there is actually a positive correlation between the certainty of position taken with the wrongness of that position. The danger, is that surety is often the rational side of the brain silencing other inputs from the emotional or intuitive side of the house, as it were. And in many decisions, especially big ones in your life, this is exactly the side that one should be listening to.

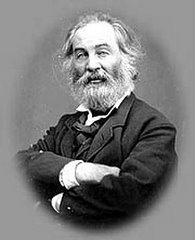

Walt Whitman had it right when he said: "I am vast; I contain multitudes." Similarly Emerson's statement: "Consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds." When confronted with this cacophony of disparate inputs from the brain we often trick ourselves into surety - a false one to be sure. It is the little attorney that resides in our rationality that spins these briefs and we accept them with great willingness. Take, for example, the experiments with people who have had their callosum calorum cut (the nerve tissue that connects the two hemispheres of the brain - done to reduce severe seizures); when through a special visual instrument different pictures are shown to the different hemispheres (each unaware of the other) and they are asked to point to what they saw, each hand points to a different picture. For example, one hand to a shovel and the other to a chicken foot. When asked to explain why these two, without exception the person will give what is to them a rational explanation: the chicken foot goes with the shovel because you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shit out of a shed. This is stated with absolute certainty. Our rational attorney will always provide us with a ready explanation and one that presents a false picture of a unified brain, even when there is none whatsoever. The need to supress inner contradictions is a fundmental property of the human mind.

Lehrer suggests the following to avoid falling into this trap of certainty. First of all, embrace uncertainty. Pretending that a mystery does not exist invites the dangerous pitfall of certainty. "Bad decisions happen when the mental debate is cut short, when an artificial consensus is imposed on the neural quarrel." This can best be done by (1) allowing yourself to entertain competing hypotheses; (2) continually remind yourself of what it is that you do not know. And finally keep in mind that you know more than you know. "The conscious brain is ignorant of its own underpinnings, blind to all the neural activity taking place outside of the prefrontal conrtex. That is why people have emotions: they are windows into the unconcious, visceral representation we process but don't perceive. The one thing that you should always be doing is considering your emotions, thinking why it is that you are feeling what you are feeling.

Monday, May 4, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment